In the summer of 2023, Saint Louis University historian Doug Boin, Ph.D., unearthed the foundations of a building in central Italy that could help recover a forgotten chapter of ancient Roman history.

It was a tense morning. Doug Boin, Ph.D., and his Italian collaborators stood by on July 31, 2023, while a skilled excavator operator carefully scraped away layers of earth near Villa Fidelia in the central Italian town of Spello in the region of Umbria.

“The team and I waited around about two and a half hours that morning for any indication that we were in the right area and that we had not wasted everyone’s time and money,” Boin said.

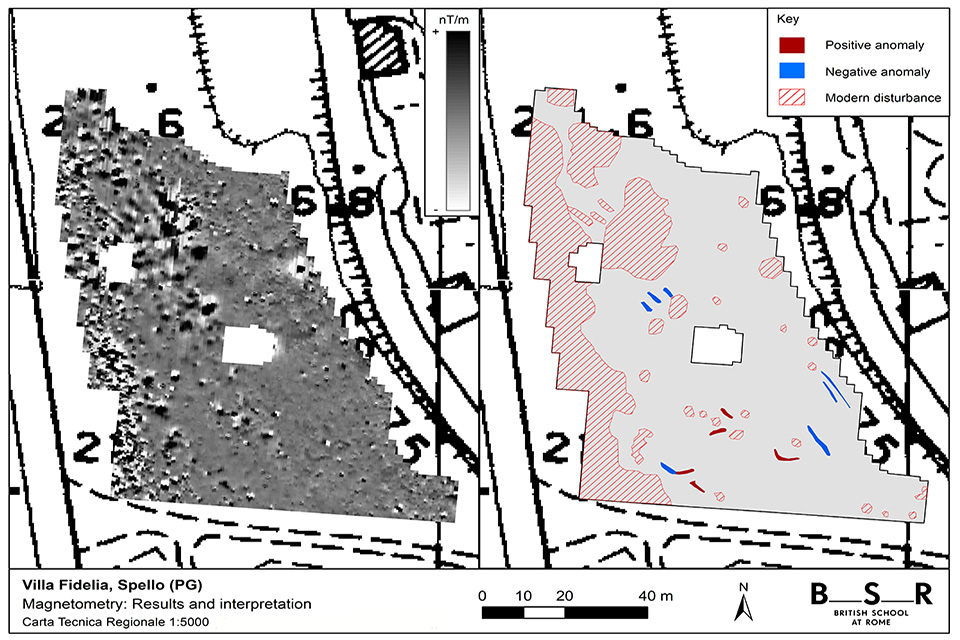

Boin and his team of archaeologists — which included independent researchers Francesco Giorgi and Danilo Nati; Stephen Kay, archaeology manager at the British School of Rome; and Letizia Ceccarelli, contract professor at Politecnico di Milano and British School of Rome research fellow — had identified their dig site using the advanced geophysical tools of ground-penetrating radar and magnetometry. These two technologies can help identify underground structures and characterize buried materials without having to disturb a single granule of soil, but the cutting-edge methods provide only estimations of what might lie beneath meters of earth. So as the hours passed on the morning of July 31, 2023, Boin and his colleagues were starting to get nervous.

“We’re standing there huddled around this five-by-five-meter trench — 7:30, 8:30, 9 o’clock in the morning — waiting for some sign that the magnetometry and ground-penetrating radar have led us to the right area. And there was nothing.”

But then, Giorgi, who has more than two decades of experience conducting archaeological digs to uncover ancient Roman artifacts in Italy, called the team’s attention to a sign of hope — a layer of pinkish soil starting to emerge as the excavator scraped away more material.

“He said, ‘This is a very good sign. Because I’ve worked in Umbria before, and the pink rocks layer is an alluvial deposit from the hillsides that usually sits on top of Roman layers,’” Boin recalled him saying. “‘So if we’re about to find anything, it would happen soon.’”

With just a few more passes of its massive metal shovel, the excavator skimmed the top of the structures the team had seen in the subterranean scans of the site. They turned out to be human-made masonry. By the end of that first morning, the team, using hand tools after the excavator had ceased its rumble, uncovered the tops of what appeared to be three thick stone walls.

Boin and his colleagues were careful to not overstate the significance of their find, but it’s hard to contain the excitement over what they may have unearthed from the Umbrian soil.

Hints of a Temple

They were digging in Umbria because of a fourth-century stone inscription that historians found in the 18th century. The 1.5-by-0.5-meter stone slab contains a message from the fourth-century Roman Emperor Constantine, who famously converted to Christianity during his rule. The communication from Constantine was a response to the Roman citizens of Spello seeking a reprieve from traveling to a faraway religious festival. Constantine granted their request and allowed them to hold their own festivities in Spello, but in return required them to erect a temple to Constantine and his ancestors, continuing a long-standing Roman tradition of the “imperial cult,” in which emperors and their families were worshiped as deities.

“The inscription always stood out because it refers to Emperor Constantine's ancestors as divine,” said Boin. “And this is a part of Roman religion, which we would classify as pagan, but it's happening at this period when the Roman Empire is trending Christian.”

Boin and his collaborators zeroed in on the resplendent, Renaissance-era property on the outskirts of Spello called the Villa Fidelia. The Villa Fidelia sits atop an ancient religious sanctuary that had been excavated by archaeologists and determined to have been used by the Indigenous people, the “Umbri,” of the area as far back as the eighth century BCE. It is also a likely origin for the stone slab that references the temple to Constantine. “That was generally the precise region that we were able to determine from the archival material where the inscription had been found,” Boin said.

Though historians had uncovered fragmentary clues to the cultural complexion of Spello in the time of Constantine from digs in and around Villa Fidelia, no one had ever located a structure that was sufficiently grandiose and properly aged to be called the “magnificent undertaking,” as referenced in the inscription, dedicated to the Christian emperor and his ancient relations.

“There was a mosaic found, in the backroom of one of the properties. There was maybe the remains of a wall that was found marking out one of the terraces in the hillside,” Boin said. “But no major monumental structure has ever been associated with it.”

So he and his team trained their sights on the large open gardens and lawns that had not been excavated. In 2019, Boin received a Beaumont Scholarship Research Award from SLU to conduct a geophysical survey of Villa Fidelia and the surrounding grounds.

“We were hoping that in the best possible case, we would find maybe a large monumental temple that dated to the period of Constantine, or in the event that maybe we were overthinking things, that there would just be some other evidence for the history of the sanctuary between its founding in Indigenous times and its transformation through the Roman period, up to the late Middle Ages,” Boin said.

Boin and his collaborators conducted ground-penetrating radar and magnetometry surveys of the Villa Fidelia and its grounds in 2021. Local archaeological officials at Spello also extended an offer to scan a parking lot across the street from the Villa, which Boin accepted.

“What came back from ... the parking lot was clearly defined Roman walls that were joined at right angles and were identified at a depth of anywhere between [1 and 2 meters] beneath the surface. And it did look promising as an ancient structure.”

So in 2023, after receiving another Beaumont Award from SLU and permission from the local authorities and the Ministry of Culture in Rome, Boin and his collaborators spent that tense late-July morning watching a skilled excavator operator scratch away millennia of history until he reached the pink paydirt. Three stone walls emerged after another two weeks of careful digging, and these ruins may serve as the most solid evidence yet uncovered of the overlap between the imperial cult and the gradual shift to Christianity during the rule of Emperor Constantine. They may be the walls of the very temple Constantine ordered the citizens of Spello to construct centuries ago.

“They were nothing like the foundations of what a potential Roman house would be, because they were twice as thick,” Boin said. “So the team ... instantly hypothesized [the excavated walls] were the interior walls and the potential exterior walls of a Roman temple.”

Layers of History

Not only did the dig beneath the parking lot reveal the remnants of a possible temple, but it unearthed clues to about 800 years of history, according to Boin. At the lowest point of the dig site, Boin and his team found small, bronze religious dedications and other artifacts left by the Umbri people around the fifth or fourth century BCE. These rare finds alone are noteworthy among archaeologists. Above that layer, the researchers found evidence of a structure that could have been either a Roman water channel or part of a fountain from the second century BCE. But the monumental structure — in the form of the three adjoining walls — most excited Boin and his colleagues.

“It was absolutely a stunning discovery,” said Ceccarelli. “For the past 300 years, historians and archaeologists have been guessing at the size, shape, and location of this ancient sanctuary space.”

Though Boin and his colleagues are careful to not yet conclude that they’ve found the temple to Constantine, if they do confirm their hypothesis, the find could represent a major signpost of the evolution from the imperial cult to Christianity in the Roman Empire. Such a material revelation in the reconstruction of Roman history is illustrative of the broader contributions of archaeology to the telling of the human story.

“The hard and fast dates of history that we use to create periods and we use to create our sense of neat and tidy chronology really fall apart when you get down to the level of daily life on the ground, especially during a period like the fourth century, when the Roman Empire is undergoing significant social, cultural, religious changes,” said Boin. “What you see in the archaeology is just how messy — literally — life was when people lived through these major moments of punctuated change. And that, I think, is just very important from a microhistorical point of view. So in many ways, archaeology can kind of come in and shake us and say, ‘You might think you know the way the story goes, but you don’t.’ That I think is the most fun part of doing the discovery. New evidence changes the way you tell the story," said Boin.

Future Digs Into the Past

The task ahead of Boin and his collaborators is to return to Spello in 2024 to further excavate the site and seek confirmation that they’ve found the temple to Constantine. The team will employ the same approach of scanning the site before excavating it in the next round of discovery, said Kay, who oversaw the geophysical surveying of the site before digging began.

“I like [that] I can be involved from the very outset through the noninvasive work [to] the excavation and then the post-excavation work, as well,” Kay said. “Ideally, together with Letizia and Doug, we'd like to slightly extend further and confirm the ground penetration radar results, but that's dependent on successful funding.”

Securing that funding is indeed essential not only to finishing up their work at Villa Fidelia, but to preserving their dig site if they can confidently claim that they’ve found the temple to Constantine, according to Boin.

“I would hope that that would be the next round of funding. Not only toward the study of the site, but toward the preservation of the site,” he said. “Because it would be so historically significant at that stage that I wouldn’t want to just walk away knowing that it’s hidden in the ground after it’s been published and reported and extensively documented. I would love, if it did turn out to be a significant find, to be able to participate in making sure that it remained a part of Italy’s cultural heritage.”

Story by Bob Grant, executive director of communications, research.

This piece was written for the 2023 SLU Research Institute Annual Impact Report. The Impact Report is printed each spring to share the successes of our researchers from the previous year and share the story of SLU's rise as a preeminent Jesuit research university. More information can be found here.