Curating Quality Resources using the Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Instruction

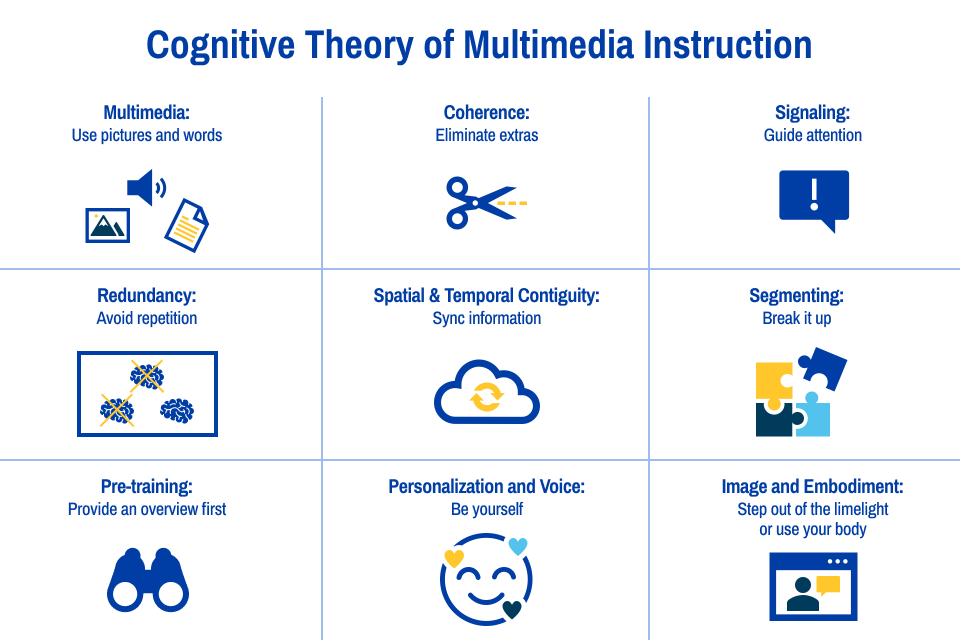

With the shift toward online modes of delivery for instructional content, the Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Instruction is an important framework for educators seeking to create or evaluate high-quality instructional videos and presentations. The theory centers on the ways in which we can reduce the extraneous cognitive load that it takes to construct knowledge, and instead have our learners focus their cognitive efforts on tasks that are more relevant to their learning. Even with the rise of high-quality third-party resources, educators have opportunities to create multimedia resources that are engaging, informative, and can result in deep learning. Below are ten general principles that can help you guide the development of these resources:

1. The Multimedia Principle: Use pictures and words

The first and most basic principle to keep in mind is the multimedia principle, which dictates that people learn better from words and pictures together than from either alone. Our brains process verbal and visual information in complementary ways, and both are necessary to integrate difficult material.

2. The Coherence Principle: Eliminate extras

The coherence principle suggests that people learn better when extraneous and irrelevant material is excluded. For educators, this means avoiding unnecessary decorations, sounds, or animations that do not directly support the instructional message. Removing such “seductive details” allows learners to recall more of the main points. For example, using an image with only relevant structures labeled rather than a detailed diagram helps learners focus on the learning objective at hand.

3. The Signaling Principle: Guide your learner’s attention

The signaling principle asserts that people learn better when cues are added that highlight the organization and hierarchy of material. Judicious use of visual indicators such as arrows or callouts, or using bolded, highlighted, or color-coded text can help emphasize key concepts and cue your learners into the structure of information. Verbal signaling can include using pointer words like, “First,” “Second,” and “Third,” or raising the volume or pitch of your voice if presenting verbally.

4. The Redundancy Principle: Avoid overloading with repetition

Learners can be overwhelmed when the same information is presented simultaneously in multiple forms. An example is when an educator reads to students directly from slides in a classroom environment. Instead, pair visuals with spoken instruction instead of having the same text on screen and words out loud. This can help ensure that each mode of presentation adds something to the learning experience.

5. Spatial Contiguity: Keep it together

The spatial contiguity principle emphasizes that learners better understand and remember content when corresponding words and images are presented close to each other in space. If a label is placed too far away from the corresponding diagram, learners spend cognitive effort trying to make the connection, which detracts from their time spent understanding. For recorded videos, rather than having a bulleted list on the left and an image on the right, use a more free-form approach to associate text and images more closely. Be sure to use plenty of signaling to make sure that learners know how to follow!

6. Temporal Contiguity: Sync your information

The temporal contiguity principle states that learners understand better when corresponding words and pictures are presented simultaneously rather than sequentially. For example, a blank diagram with text that appears as you discuss each branch of an artery or each step in a physiological mechanism would be following the principle of temporal contiguity, as would drawing a diagram and explaining it as you go.

7. The Segmenting Principle: Chunk it up

The segmenting principle suggests that learners benefit when information is divided into smaller, manageable segments rather than presented as a continuous stream. This principle recognizes that learning is a process, and “chunking” information allows learners to digest content in stages. For example, rather than presenting a one-hour recorded lecture, a series of shorter, 10-minute videos that each cover a specific learning objective can help learners grasp and retain information more easily.

8. The Pre-training Principle: Spoil the ending

The pre-training principle posits that we learn better when we already have a basic scaffold upon which to build new knowledge. Spend a small amount of time providing learners with a brief overview of key concepts and terms or the learning objectives so that they can activate prior knowledge in order understand better and retain new information.

9. The Personalization and Voice Principles: Be yourself

People learn better when words are spoken in a conversational style rather than a formal style. When learners feel that the educator is talking to them, they are more likely to see the author as a conversational partner and will try harder to make sense of what the author is saying. Likewise, voiceovers spoken by real people lead to better learning than computer-generated voices.

10. The Image and Embodiment Principles: Step out of the limelight unless necessary

The image principle suggests that people learn better from high-quality, relevant visuals than they do from videos that over-emphasize a speaker. The reason is because in these videos, learners may focus on the speaker rather than on the informational content. In contrast, the embodiment principle suggests that instructors who use their bodies as part of their instructional communication can be more effective. For example, demonstrating a muscle’s actions or drawing on a whiteboard while explaining are both high-embodiment activities.

Each of these principles has boundary conditions that exist around individual differences in knowledge, differences in the complexity of instructional content, and the pace and context of a lesson. For example, spatial contiguity may be particularly important when learners are unfamiliar with complex material – conditions that all exist for learners in a preclinical anatomy class. More experienced learners, like a surgeon taking a continuing education course on brachial plexus injuries, may be able to learn from a diagram alone, without added text. Additionally, to ensure that all learners can benefit equally from your efforts to reduce cognitive load, it’s important to make sure that your content is visually accessible in terms of being high contrast, and that learners have the ability to turn accessibility features, such as closed captioning, on or off.

As the landscape of medical education continues to evolve, it is important to keep in mind that knowledge is not simply transferred from instructor to learner, but rather is constructed using cognitive processing. Aligning instructional strategies to the ways in which learners process information can help manage us to create learner-centered resources that help manage extraneous cognitive load and support deep learning,

Aidan Ruth, Ph.D. is Associate Professor in the Center for Anatomical Science and

Education at the Saint Louis University School of Medicine. Aidan's areas of professional

interest include humanism in anatomy education, pre-professional anatomy outreach,

and metacognitive training. Aidan can be found on LinkedIn, or contacted via email.

Aidan Ruth, Ph.D. is Associate Professor in the Center for Anatomical Science and

Education at the Saint Louis University School of Medicine. Aidan's areas of professional

interest include humanism in anatomy education, pre-professional anatomy outreach,

and metacognitive training. Aidan can be found on LinkedIn, or contacted via email.