SLU Researchers to Digitally Map Lived Religion in St. Louis Region

Maggie Rotermund

Senior Media Relations Specialist

maggie.rotermund@slu.edu

314-977-8018

Reserved for members of the media.

ST. LOUIS - With a $400,000 grant from the Henry Luce Foundation, researchers at Saint Louis University will create a digital portrait of religious life in the St. Louis area.

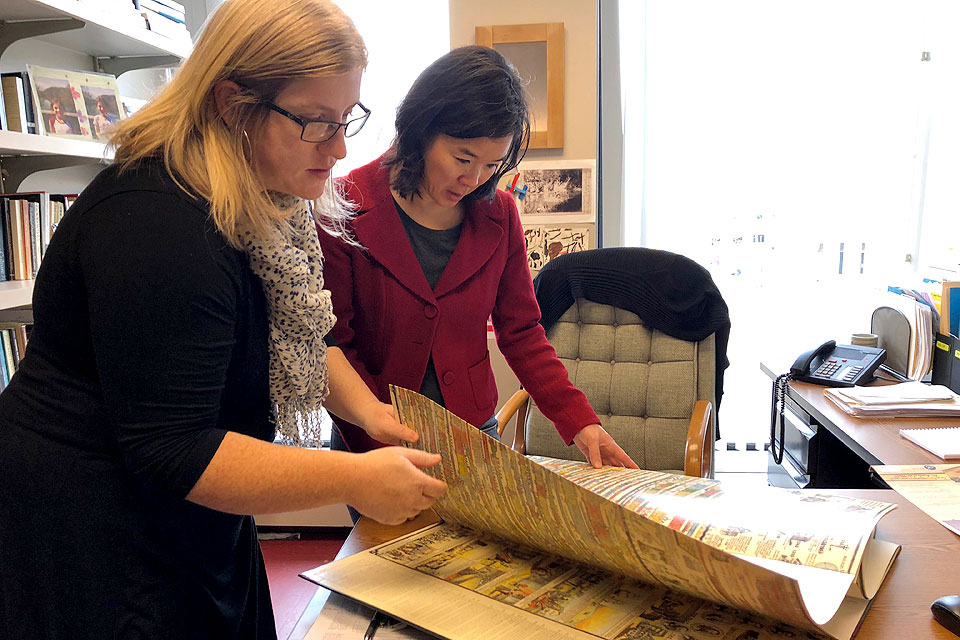

Rachel Lindsey, Ph.D., assistant professor, and Pauline Lee, Ph.D., associate professor, both in SLU’s Department of Theological Studies, will use the funds to create a digital database of religious life in St. Louis which includes interviews, profiles, maps and media content.

“Our hope is to tackle preconceived notions about this thing we call ‘religion’,” Lindsey said. “What does the study of religion look like when we shift public attention from shared beliefs (be they theological, moral, or civic) to shared spaces? And more than that, what does religion do in these spaces?”

The project begins by asking people to think outside the box and relinquish specific definitions of religion to delve into details of lived experience.

“What does religion look like to you? Taste like? Smell like?” Lee asked. “What are people doing to live their religion? That is some of what we are seeking to map out.”

That map includes brick and mortar churches, mosques, temples and synagogues, but it will also feature places where people live their religion outside of a place of worship as well as closer scrutiny to how religion is woven into local cultures, regardless of personal faith traditions.

“Think of civic events and places - Festival of Nations in Tower Grove Park, the Gateway Arch, baseball at Busch Stadium, even protesting and voting - and we don't usually think ‘religion,’” Lindsey said. “But what we are finding is that people are making connections between their religious lives and the city all the time. And that even people who don't identify as religious are often shaped by the religious histories and cultures of the city.”

The research team will create a digital lived religion framework which will capture sights, spaces, and sounds.

The findings will be available to the public on a new web site created by SLU’s Walter Ong, S.J., Center for Digital Humanities.

“We are hoping to push the edge of what is currently available by mapping the diversity of religious faiths within St. Louis and its history and create a database of scholarship,” Lee said.

Teams of student researchers will participate in mapping and interviewing subjects. The project also supports research and teaching fellowships, including a graduate research assistantship, to build interdisciplinary collaboration. The project’s research questions might look different from what we typically associate with religion and theology.

Instead of starting with questions of belief and doctrine, Lindsey and Lee want to know about objects, spaces, practices, food, music, and personal history, among other potential topics.

These questions will yield a description of each place, and help paint a picture of its connection to a faith tradition, the city itself, and, ultimately, what religion means in St. Louis and to St. Louis.

The statue of St. Louis in Forest Park is an example of a monument that can have several meanings, Lindsey and Lee said. It can be symbolic both of our civic religion as the namesake of the city or it can be a symbol of Catholic faith. It also invokes darker histories of violence.

“People can relate to something as a religious figure as well as a civic memorial,” Lindsey noted.

It is this fluctuation of meaning that their project will seek to map by focusing closely on the rich history of the St. Louis region.

In many ways, mapping religion in St. Louis can provide a framework to how the city developed and how groups of people migrated to the area and where they settled.

“St. Louis is never static - it is always changing,” Lee said. “It’s exciting to think through the history of religions here and what that has meant to the city at different points in its history.”

To this end, their research project involves close collaboration with community partners, from faith traditions to journalists, artists, museums, and civic leaders. Their first community event, planned for the spring, will bring professional artists into conversation with local communities through a crowd-sourcing photography exhibit.

Ultimately, the focus on St. Louis is a case study for thinking about the translation of local religion--with all the textures of lived experience--into digital products and platforms.

For Lindsey, this aspect of the project echoes what she saw among nineteenth-century Americans who were encountering the then new technological marvels of photography. Both researchers were also inspired by SLU’s history of pioneering new technologies in research and teaching, from the university’s early adoption of the “radiophone” in 1921 to the founding of the Center for Digital Theology at the turn of the new century.

The three-year public theology and digital humanities project is one of a handful funded this year by the Luce Foundation’s Theology Program. Other universities funded this year include Morgan State University, Northeastern University, Ohio State University and Princeton University.

Assisting with the project is research fellow David Justice, a first-year Ph.D. candidate who studies twentieth-century race relations through the lens of liberation theology, African-American religious history and social justice.

Founded in 1818, Saint Louis University is one of the nation’s oldest and most prestigious Catholic institutions. Rooted in Jesuit values and its pioneering history as the first university west of the Mississippi River, SLU offers nearly 13,000 students a rigorous, transformative education of the whole person. At the core of the University’s diverse community of scholars is SLU’s service-focused mission, which challenges and prepares students to make the world a better, more just place.