SLU Researchers, Partners Train Bystanders to Speak Up to Stop Child Mistreatment

Carrie Bebermeyer

Public Relations Director

carrie.bebermeyer@slu.edu

314-977-8015

Reserved for members of the media.

12/10/2019

It’s a gut-wrenching experience. While shopping or eating out, a nearby parent’s voice starts to raise, their patience exhausted with a child. Initial empathy turns to nervous monitoring as voices become harsh, language becomes threatening, arms are yanked and children swatted. As emotions, words and behaviors escalate, stakes feel high and people nearby may freeze with uncertainty, only to find themselves second-guessing their own response or inaction with guilt and regret afterwards.

SLU’s Nancy Weaver, Ph.D., has been there.

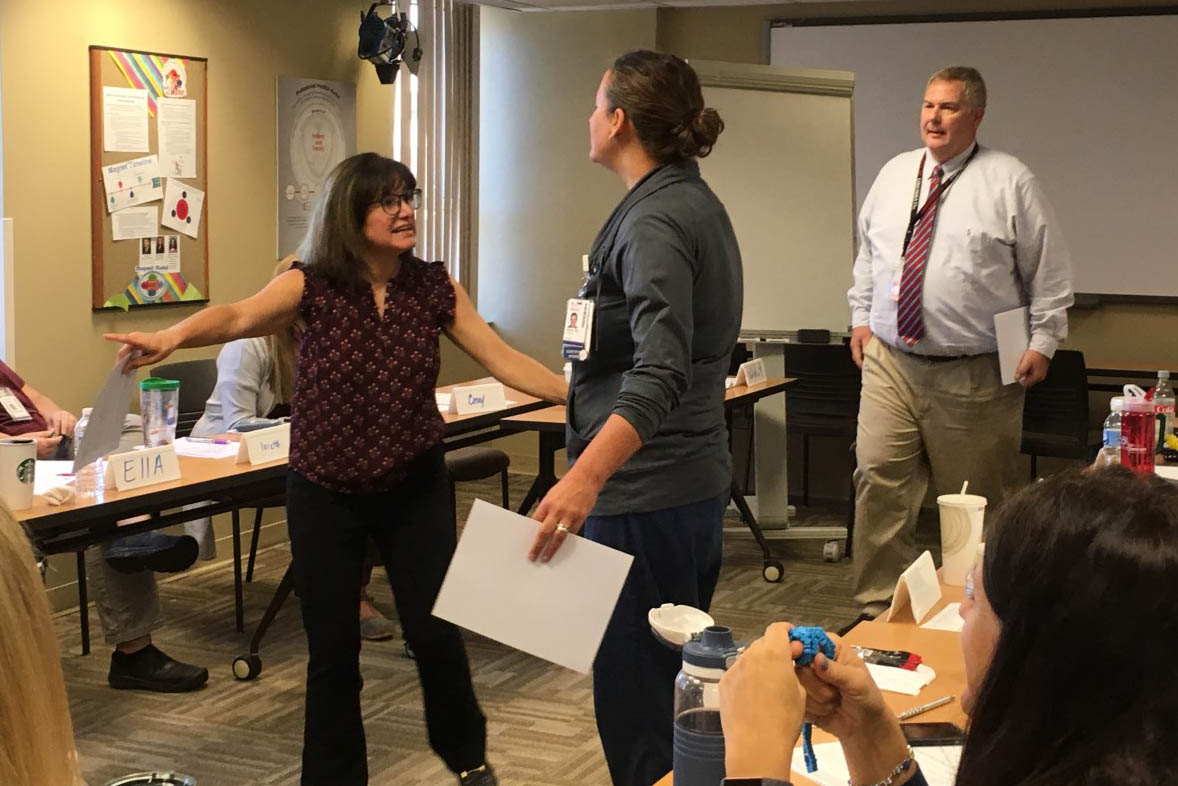

Weaver, who is professor of behavioral science and health education and associate

dean of academic and faculty affairs in Saint Louis University’s College for Public

Health and Social Justice, shared her own experience at a recent training session

for bystanders.

She was eating dinner with her family at a local pizza parlor, Weaver recounts, when

the entire restaurant became hushed as a grandmother and two grandchildren at a nearby

table grew louder in a heated moment. Concerned that the situation was escalating

and noticing that no one else seemed inclined to take action, Weaver joined the family

at their table and said, “It looks like you guys are struggling.”

The simple act of reaching out unleashed the floodgates for the overwhelmed grandmother

who visibly softened and began to share various stressors – the children’s mother

delayed at work, kids eating out of vending machines all day, the short window to

get dinner for the kids before taking them along to her second job, a son-in-law out

of town and running late – that led to the current moment with emotions running high.

“That sounds rough. That sounds difficult. I hope your day gets better.”

Weaver’s act of support through listening diffused the high energy of the moment. The restaurant began to buzz with conversation again. Later, a manager would come over to thank Weaver for her intervention, saying he hadn’t known what to do.

Afterwards, Weaver reflected on the situation, wondering if she’d done the right thing and surprised that no one else responded. She realized that more people would be inclined to reach out in similar situations if they felt more confident about how to intervene.

Support is usually welcome. Judgment isn’t.

Nancy Weaver, Ph.D.

Several years later, with support from Missouri Foundation for Health, Weaver and

a host of SLU collaborators and partner institutions, including SSM Health Cardinal

Glennon Children’s Hospital, FamilyForward, Safe Connections and UPBrand Collaborative,

have developed a training course and launched a website to give bystanders tools to

feel more confident in responding.

Borrowing from an approach used to train bystanders to intervene to prevent sexual

assault, the team developed a program called Support Over Silence for KIDS. This strategy gives bystanders the skills to confidently defuse a challenging moment

between a caregiver and a child.

Based on research and feedback from many training sessions, the team has launched a website with resources for the public. Individuals and groups who are interested in learning more about Support Over Silence for KIDS training sessions can contact the program through the website.

Tense moments often happen in places where stress is high, where money is involved, like the checkout line, and when kids and parents are hungry, tired or anxious, such as grocery stores, airports or doctors’ offices. Behaviors can range from ignoring a child, speaking harshly, threatening, rough physical handling or physically harming a child.

At the recent training session held at SSM Health Cardinal Glennon Children’s Hospital, the room full of healthcare providers nodded in recognition after hearing Weaver’s personal story. As participants discussed situations they’d witnessed, they voiced empathy for parents who were struggling, with many noting they’d been in similar situations themselves.

“Some people never get a break,” was a shared sentiment.

Weaver offered a framework for thinking about these situations.

“We probably won’t ever know why the interaction is happening. The mistreatment in

public could be very consistent with what’s happening at home or it could be just

a difficult moment,” Weaver said. “But, we don’t need to make a judgment about whether

a caregiver is a good or bad parent. In the moment, our only job is to notice the

situation and take some action to support the caregiver and child.

“Don’t feel obligated to fix parenting,” Weaver said. “In this moment, I’m only requiring

of myself that I reach out and offer support. You’re not berating parents or calling

out deficiencies.”

What doesn’t work? The side-eye, Weaver says. A go-to for many, this attempt to put

a parent on notice is ineffective.

“Support is usually welcome. Judgment isn’t,” Weaver said.

When a heated moment occurs, see it as your responsibility to intervene, Weaver says. Take a deep breath. Then, think about the acronym KIDS which offers several possible strategies for bystanders.

Keep to yourself or share Kind words.

If it’s a passing moment, you may simply choose to move along your way, or provide supportive and kind words. Say something encouraging to the caregiver, such as “You’re doing great. Kids are so curious at that age!”

Intervene Directly.

Intervening directly might include a specific ask, such as reaching out to a caregiver to say “It looks like you’re having a hard time. Anything I can do to help?” Or “We’ve all been there. Is it okay if I get a snack for you all?”

Distract.

Distraction can be directed toward a child or parent, with “I like your shoes.” Or by commenting on something in the store, “The granola bars are on sale!” or singing a song.

Seek Help.

If a situation is volatile or you are concerned for a child’s or your own safety, seek help from professionals. Other people can also help you overcome your own barriers for reaching out.

Finally, for those who worry that intervening may make things worse for a child, Weaver

shares this perspective.

“In some ways how we treat children is thought of as a private issue, and people

are hesitant to intervene in someone else’s parenting,” Weaver said. “But it’s so

important for a child to see another adult offering a different narrative.

“It’s amazing to me. As you start hearing stories of child abuse, you hear how normal it becomes for a child with no other models. Children who were abused grow up and say ‘If one person, one adult had told me it’s not normal to be berated or hit, told me that I mattered, it would have made all the difference.’

“The community has a collective responsibility to protect children, to show children that someone cares, that they are not invisible,” Weaver says. “In this moment, it is not your job to teach or judge, just to support.”

Other members of the project team include Terri Weaver, Ph.D., professor of psychology

at SLU; Timothy Kutz, M.D., associate professor of pediatrics at SLU and a child abuse

pediatrician at Cardinal Glennon Children’s Hospital; Vithya Murugan, Ph.D., MSW,

assistant professor of social work at SLU; Karen Nolte, chief executive officer at

FamilyForward; Jessica Dederer, MHA, chief development officer at FamilyForward; Cynthia

Danley, chief development and marketing officer at Safe Connections; Jess Cowl, MSW,

LMSW, former assistant director for crisis and prevention at Safe Connections; and

Zenique Gardner-Perry, prevention education manager at Safe Connections. Research

assistants at SLU’s College for Public Health and Social Justice included Allie Diltz,

Jessica Fry, Tatiana Gochez-Kerr, Savannah Jordan, Lindsay Maunz, Yit Mui Khoo, Gabriella

Mujal and Meghan Taylor.

Support Over Silence was funded by the Missouri Foundation for Health, grant number

16-0421-CF-16.

For more information about Support Over Silence for KIDS, visit: https://supportoversilenceforkids.org/.

Saint Louis University College for Public Health and Social Justice

The Saint Louis University College for Public Health and Social Justice is the only academic unit of its kind, studying social, environmental and physical influences that together determine the health and well-being of people and communities. It also is the only accredited school or college of public health among nearly 250 Catholic institutions of higher education in the United States.

Guided by a mission of social justice and focus on finding innovative and collaborative solutions for complex health problems, the College offers nationally recognized programs in public health, social work, health administration, applied behavior analysis, and criminology and criminal justice.