Ruined for Life

04/22/2024

Think back to when you were graduating from Saint Louis University. Did you have your first real job lined up, or an internship to get you there? Maybe you’d planned to travel abroad. Maybe you anticipated a typical summer, before heading to graduate, medical or law school.

What if, instead, you’d decided to spend the next year serving?

That’s what Jesuit Volunteers do. And what many SLU alumni choose.

Saint Louis University is one of the top five producers of volunteers who work with two Jesuit Volunteer organizations: the Jesuit Volunteer Corps (JVC) and JVC Northwest.

For these Billikens, service is a full-time job. They spend 40 hours a week doing direct service at more than 200 partner agencies that address a multitude of issues — from hunger relief to environmental stewardship to legal services. They receive a modest monthly stipend, as well as health insurance and housing. In their free time, they live with other Jesuit Volunteers (JVs) in reflective, cooperative communities. They keep house together and meet weekly for spiritual and bonding activities. They focus on four core values: community, simple living, spirituality, and social and ecological justice.

It’s service but also solidarity.

“We don’t view ourselves as a ‘service program.’ We’re a service and formation program,” said Shivany Trujillo (A&S ’08), director of admissions for JVC. “You’re living with each other. You’re spending a lot of time on JVC values. And you’re tied to the communities you serve because you’re right there. Your clients might be your neighbors. You’re taking the bus; your clients are taking the bus. That’s a big part of the success of our program.”

That kind of immersion obviously changes a person.

To borrow a phrase from the founder of the Jesuit Volunteers, Jack Morris, S.J., a year as a JV will leave you “ruined for life.”

“You’re going to be doing wonderful things, getting to know underserved communities and learning about justice in the world. But it’s also a way of discerning and figuring out what you really want to do with your life,” Dr. Bobby Wassel said.

Wassel (Grad Ed ’09, ’17) is the director of SLU’s Center for Social Action. He’s worked on community engagement, service and justice issues at the University for nearly 20 years. Having done service after college with an organization that modeled itself on JVC, he knew firsthand the value of the experience and has promoted it to SLU students from his earliest days on campus. Every November, he helps coordinate SLU’s Year of Service Fair, bringing dozens of organizations to campus.

“Participation in post-graduate service has dropped nationwide for many reasons, but Billikens continue to consistently choose this option,” he said. “I think it speaks directly to our mission.”

Both JVC and JVC Northwest accept applications during four different rounds a year, with the earliest deadline in December. This academic year, the sibling organizations are offering a common application to streamline the process.

Seven members of the Class of 2023 began their placements in August and will serve through July 2024. Then, they’ll join the network of more than 12,000 Former Jesuit Volunteers (FJVs).

Below, meet four SLU alumni FJVs, and learn how they were “ruined for life.”

Dr. Katy Dominick

JV Placement

Christian Senior Services in San Antonio, Texas, 2012-13

I assessed homebound patients for Meals on Wheels and other services they could receive from the nonprofit.

I knew medicine was where I’d end up — but I wanted more than the direct route to being a physician. School can be very black and white, but life is in the gray. I felt fortunate to have a comfortable home and go to good schools; I wanted to experience the gray.

I felt like JVC would help me provide for my patients later — not just the black and white of being a physician, but everything that comes with really caring for people.

My JVC job helped me become the physician I am; but how I feel about the world — I learned that through the community at the church where we lived in the convent.

Six out of the seven of us JVs were raised Catholic. And it’s hard not to go to church when you can see it from your kitchen door. Every Sunday, a family cooked breakfast you could buy at church. If we helped, we got a free plate: homecooked Mexican food!

One of the other JVs was the social worker for the church and ran their youth group. We all went, whether they were shooting hoops in the backyard or had a field trip. I coached Catholic Youth Organization basketball. We picked our players up, put them in my LeSabre, took them to the games and back; their parents might not be able to. We were constantly doing stuff with people who we weren’t necessarily assigned to serve.

I was raised in a quintessential Irish Catholic family. I had no experience with other religions prior to JVC. It was eye-opening from a spiritual standpoint.

Halfway through, we decided to go to a different church to see what it was like. One of the other JVs was placed at a Presbyterian church that ran a teen home. Sometimes, we would go to church there with the teen moms. And we befriended other homes that were similar to JVC, a Mennonite home and an Episcopalian home.

JVC awoke a spirituality in me. I believe in God, and I also believe in social equity and doing good for other people.

I was naive. I found people living in squalor; they live with people who are supposed to be taking care of them, but they’re not. I learned what people do to survive and why they do the things they do under certain circumstances.

I left JVC with a lot of questions, especially trying to understand why there is inequality in the world. How do I help?

Now I work in St. Clair County [in Illinois]. I feel like I make a better connection with patients because I can understand and empathize with why they’re doing what they’re doing. “Why aren’t you taking this medicine? We’ve talked about this.” What I witnessed in JVC helped me understand the why. And then I say, “Let’s meet in the middle.”

Kevin Finn

JV Placement

Catholic Community Services in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, 1993-94

I did emergency assistance work with people needing help with rent, utilities, etc. I also helped in a family homeless shelter and did prison ministry.

I didn’t know what I wanted to do, didn’t declare a major until I was a junior, and psychology was the only major I could still finish in four years. But what do you do with an undergrad degree in psychology? It doesn’t rule you out for any job, but it doesn’t get you many jobs either.

I’d gone to a Jesuit high school, and I had been big into volunteering. JVC was a way of continuing that while deferring my student loans and giving myself another year to think. I knew I wanted to do something related to assisting people in poverty.

It says a lot that JVC was my first experience working on the issue of homelessness, and I’m now the founder and CEO of an organization that oversees services for the homeless in greater Cincinnati. It’s my life’s work, something that I didn’t know anything about before JVC.

My very first client was a woman with 10 children, and her utilities were about to be shut off. If you lived in public housing, if utilities got shut off, you got evicted. I had been in Baton Rouge for three days — and it was my job to figure out how to help her with that serious situation.

I was lucky to live in a house of JVs who took the principles of JVC seriously, particularly living a simple lifestyle. Every one of us came from a reasonably wealthy family; we had credit cards in our pockets we could have dipped into, but we chose not to.

We had “blackout night” once a week when we wouldn’t use electricity. This was partially to lower our bill, but since I was working with people whose utilities had been shut off, it was such a valuable experience. It gave me perspective on the experiences of the people I was trying to serve.

Very hard. We got paid $205 a month, which had to cover everything but rent: our utilities, food, transportation, all entertainment.

I met my now-wife, Julie (Lynn) Finn (DCHS ’93), at SLU. Occasionally, we would meet halfway on weekends while I was in JVC. To do this, I had to sell my blood plasma for gas money. Again, a perspective on poverty I never would have had otherwise.

The other JVs I served with, all three are in education and one is also an Episcopal deacon. Each of us went into a profession in which we are more concerned about helping others than making a bunch of money. It’s hard to know if that’s JVC’s impact on people or if those are the people that go into JVC — but no doubt JVC helped make us who we are.

JVC is an incredible short-term opportunity to do something you’ll never be able to do so easily later — a chance to broaden your perspective on what you will do with the rest of your life.

Whatever else you’re going to do, it can wait a year.

Maria Garcia

JV Placement

Catholic Migration Services in Harlem, New York, 2019-20

I was essentially a legal assistant for the removal defense project team. I gathered research and translated documents, helping clients apply for asylum.

I found out about the Jesuit Volunteer Corps in high school, and then it was always in the back of my brain. When I was a sophomore at SLU, I went to the Ignatian Family Teach-In and got to lobby the U.S. Congress. My junior year, I started thinking, maybe this is something for after graduation; I don’t think I’m ready to go to grad school or to work. I’d been part of SLU’s service-oriented Micah Program learning community, and I’d done a lot of service at SLU — that was something I wanted to continue. And I’ve always been passionate about immigrant rights and migration to the United States.

Eye-opening. I’m first generation American, half Filipino, half Guatemalan. My parents were immigrants. It was interesting to see people who have the same ethnic background as mine come to the United States. I went into JVC bright-eyed and bushytailed, and then got into some tough stuff. Specifically, the women, the domestic abuse they endured ... I was not prepared for that. I would translate documents and read horrific stuff that people had gone through, gaining really intimate knowledge of people I didn’t know. It was challenging.

My community lived on the third and fourth floors of an old convent. We each got a room of our own, and we had a rooftop we could see Yankee Stadium from. It followed the JVC value of simple living, but it was still such a cool opportunity. I won’t ever be able to live in New York rent-free again!

Living in community — those are the most intimate moments you have with people. Eight people is a lot for an intentional community, but every night, we made the effort to have a meal together. We had different schedules and were coming from different parts of New York, so we’d all have dinner at 9 p.m. It was nice to come home to people who knew what you were going through because no one else could; most of our friends were working or in school. But we had each other to lean on through tough days.

Because we were in New York during the beginning of the pandemic, only five of us ended up staying the whole year. We stayed in the house most of the time — but luckily, we had the roof to go up to for fresh air. We built a lot of trust to support one another through that year.

One of the attorneys I worked for texted me not long ago: “Remember that application you prepped right before COVID-19?” I remember it vividly. It was announced that COVID was happening and that we may have to be gone for like two weeks. But the attorney wanted to get this application in, just in case. I stayed late to help, and I delivered it to the immigration office. And it finally got approved! The person received asylum, which is amazing. And the fact that the attorney circled back with me — it meant a lot.

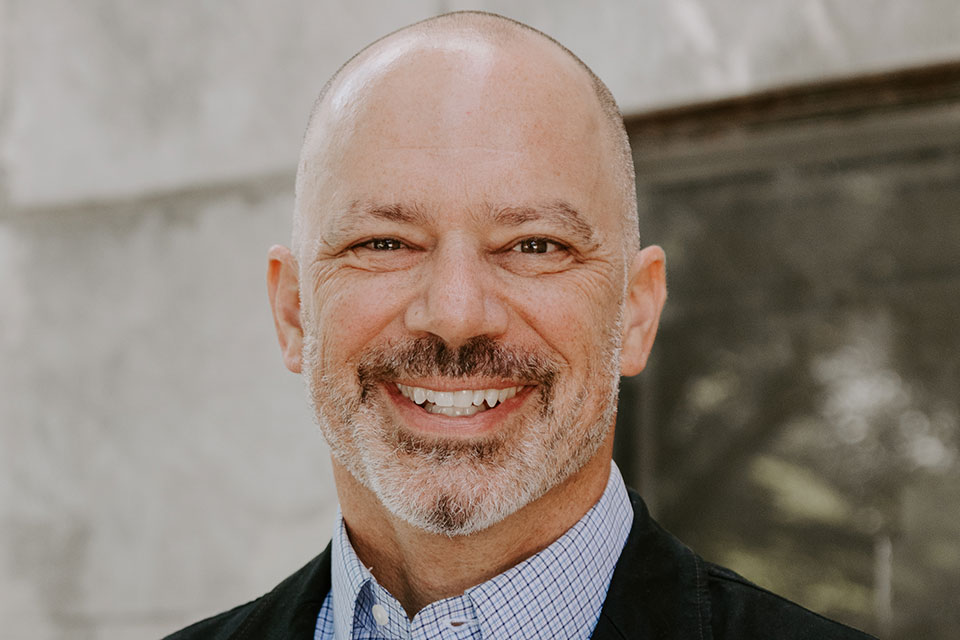

Abe Grindle

JV Placement

St. Labre Indian School in Ashland, Montana, 2006-07

St. Labre is a Catholic school that serves two Native American communities. I worked with one other JV in the high school dormitory, where about 60 students stayed. From 2 to 10 p.m., we tutored and mentored the kids.

Originally, I applied as a backup. The only graduate program I was interested in was at MIT, and I knew it was a bad idea to have just one risky option.

However, the more I learned about JVC, the more taken with it I became. When else would I have the opportunity and the flexibility to take a year and learn so much about the social justice issues in our country — the real dynamics and realities on the ground?

I was offered a scholarship at MIT but deferred it because I felt like JVC was something I needed to do.

I’d always felt a call and obligation to serve. And I wrestled with how to balance that with my passion for engineering and where my life seemed to be headed.

This felt like a unique opportunity to explore that other path in a temporary setting. I’d done co-op programs — stints at NASA facilities, having a hands-on, immersive experience. And now I had the chance to have that type of experience in a service environment.

I figured I should at least explore it: Is this actually more of my vocation than I thought? It was kind of a discernment process for me, in the classic Ignatian tradition.

Challenging but in a way that was, generally speaking, very healthy. Living with others and learning how to navigate compromise is hard. It’s actually great training for marriage — or any relationship! Personal growth is hard. It means learning things about yourself that you might not like or expect. Learning how policy and government affect people is also hard. It can be depressing, sad, difficult. But closing one’s eyes and staying away? I would argue that’s much worse.

I’m in a very different place in my life today than I ever imagined I would be, in significant part because of my JV experience.

I did go on to MIT to do a dual-degree master’s in aerospace engineering and public policy. But I had this even deeper interest in the importance of public policy to address social justice challenges. Long story short, while I was at MIT, new career opportunities came into my field of vision, including this world of strategy and management consulting for social-impact organizations.

I served on the Jesuit Volunteer Corps national board for several years, and one of the other JVs on the board was a Goldman Sachs executive. He said, “When I’m hiring, this kind of experience is incredibly valuable and really sets applicants apart.” If I could do one thing to improve the U.S., it would be to have a mandatory year of service for everybody, where people are put in a place and with people who are different from them and where they come from. That lived experience — it’s phenomenal.

There is no better holistic opportunity to form yourself as a citizen of this country and this world as JVC offers.